A Snapshot of Postsecondary Access and Opportunity in California

Published Oct 2025

Ensuring students from all backgrounds can access valuable postsecondary opportunities is critical to meeting the national imperative for an educated, resilient, and diverse workforce. Black, Latinx, Indigenous, Asian American, Native Hawaiian, Pacific Islander, and first-generation students and students from low-income backgrounds often face systemic barriers to accessing and succeeding in higher education. These barriers include limited college counseling and planning resources, inequitable admissions practices, and unclear degree pathways. These obstacles are beyond students’ control, but they can be removed or mitigated by institutional leaders and state policymakers.1

Improving access to opportunity for students from historically marginalized backgrounds can be done in several ways. In 2023, however, the Supreme Court’s Students for Fair Admissions (SFFA) v. President and Fellows of Harvard College decision limited the ways in which colleges and universities can use race-conscious admissions practices nationwide.2

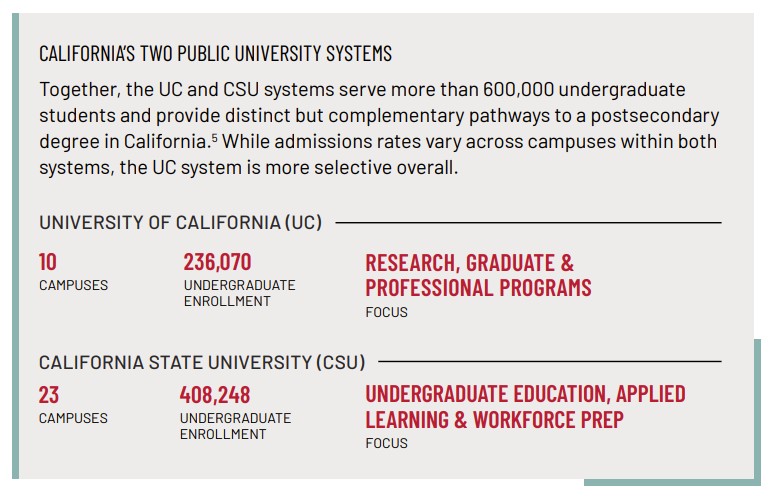

While this ruling poses new challenges for many states and institutions seeking to expand opportunity, California state and college leaders have navigated this landscape for nearly three decades. In 1996, California voters approved Proposition 209, a measure that led to the elimination of affirmative action in admissions programs. Previously, these programs had helped foster greater student body diversity at the University of California (UC) system, the state’s most selective public university system.3 The effect was stark: enrollment of Black, Latinx, and Native American students at UC’s most selective institutions fell sharply after Proposition 209 was enacted in 1998. The University of California, Berkeley, and the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA) campuses experienced 50 percent and 40 percent declines, respectively.4

Since those enrollment declines, California leaders have implemented strategies that have yielded progress in addressing them, though more work remains. This brief offers a snapshot of several strategies the state has employed to expand postsecondary access without race-conscious policies or practices. Drawing on conversations with K–12 and college access practitioners, researchers, and advocates in the state, we highlight what has worked, where challenges remain, and what lessons policymakers in other states can learn as they chart their own paths forward in the post-SFFA era.

Since those enrollment declines, California leaders have implemented strategies that have yielded progress in addressing them, though more work remains. This brief offers a snapshot of several strategies the state has employed to expand postsecondary access without race-conscious policies or practices. Drawing on conversations with K–12 and college access practitioners, researchers, and advocates in the state, we highlight what has worked, where challenges remain, and what lessons policymakers in other states can learn as they chart their own paths forward in the post-SFFA era.

What steps are being taken to expand college access in California?

While no single policy change can eliminate the many barriers historically marginalized students face in pursuing a college degree, California’s approach illustrates what deliberate and sustained action can accomplish in a race-neutral context. Three strategies stand out:

- Strengthening clear pathways from high school to college and career

- Investing in robust data infrastructure

- Rethinking recruitment, admissions, and enrollment strategies at selective institutions

1. Strengthening clear pathways from high school to college and career

Expanding entry points into postsecondary education helps ensure all students, regardless of background or circumstance, can earn a degree and enter the workforce with the skills needed to thrive. California has invested in multiple pathways that create stronger bridges from high school and community college to four-year degrees and careers.

Putting students on an early college trajectory

Dual enrollment programs can help students earn college credit while in high school, jumpstarting their college journey and building confidence that they belong in higher education. Studies show that dual enrollment participants are more likely to enroll in, persist through, and complete college.6 Roughly one-third of the state’s entire high school class of 2025 took dual enrollment coursework, though participation varies across racial and ethnic groups.7

To improve access to dual enrollment programs, the state created the Career and College Access Pathways (CCAP) Grant, which incentivizes partnerships between local education agencies and community colleges.8 Courses are taught at local high schools and tuition, fees, and materials are free for students. CCAP has grown rapidly compared with traditional dual enrollment coursework: Of the students who participated in dual enrollment between 2024-2025, 45 percent did so through CCAP. Unlike traditional dual enrollment programs, CCAP’s demographics closely resemble the state’s K–12 population (56 percent Latinx, 13 percent Asian, and 4 percent Black).9 And outcomes are strong. Eighty-two percent of CCAP students enroll in college, compared with 66 percent of high school graduates statewide.10 California invested $200 million in 2022 to expand dual enrollment and is currently exploring legislation to eliminate logistical barriers and broaden dual enrollment pathways for students.11

Improving transfer student pipelines

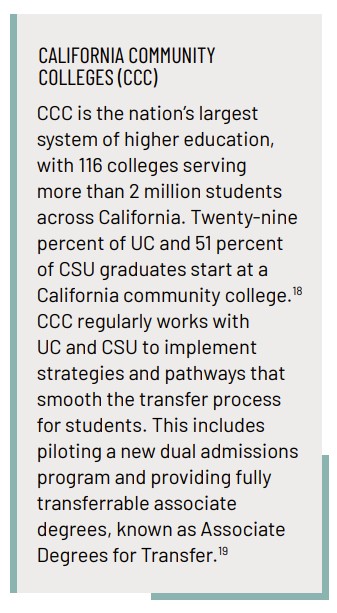

While California high school students follow a common set of curricular requirements to ensure eligibility for both the UC and CSU systems, community college students have had to face a confusing constellation of transfer requirements that vary by system and campus. This complexity creates a barrier to equitable access to four-year degrees.  In 2022 alone, more than half of Black and Latinx high schoolers who enrolled in a college after completion, enrolled in a California Community College, making the transfer pathway a critical route to four-year institutions.12 To help address some of these challenges, the state has introduced initiatives that aim to improve transfer pathways into its public systems.

In 2022 alone, more than half of Black and Latinx high schoolers who enrolled in a college after completion, enrolled in a California Community College, making the transfer pathway a critical route to four-year institutions.12 To help address some of these challenges, the state has introduced initiatives that aim to improve transfer pathways into its public systems.

These reforms have made the transfer pipeline more navigable, opening multiple pathways to higher education—particularly for Black and Latinx students. California has encouraged institutional collaboration, and it should continue to support these partnerships and promote greater alignment across its three systems to ensure seamless pathways to a four-year degree.

These initiatives include:

- Associate Degree for Transfer (ADT): While most of California’s community college students intend to transfer, less than half do so within six years of their initial enrollment, and those who do transfer often arrive with credits that do not end up counting toward their degrees.13 A student who earns an ADT through CCC is guaranteed admission to a CSU campus, or other participating university, as a college junior.14 Research shows ADT has helped streamline the process: Students graduate with 6.5 fewer excess credits than peers who pursue traditional associate degrees. And at CSU, more than 50 percent of ADT transfer students graduate within two years.15

- California General Education Transfer Curriculum (CalGETC): CalGETC is a standardized education pathway that simplifies transfer requirements across institutions and systems, eliminating redundancies, and is designed to support timely degree completion for transfer students.16

- Dual Admissions Pilot: The California legislature has directed UC and CSU to partner with CCC on a dual admission pilot that would guarantee eligible students a spot in one of the state’s four-year systems.17

Building pathways to college and career

Today’s college students continue to weigh job opportunities when deciding whether and where to enroll in college.20 California is responding with investments that tie education more closely to workforce opportunities.

In 2022, the state approved nearly a half billion dollars for the Golden State Pathways Program (GSPP), which creates structured pathways from high school into fields deemed “high-wage, high-skill, high-growth areas.” This includes technology, health care, education, and areas aligned with regional market needs.21 Legislation requires these academically rigorous pathways to include career-technical coursework, a work-based component such as an internship, and at least 12 transferrable college credits earned through dual enrollment, Advanced Placement (AP), or International Baccalaureate (IB) coursework.22

GSPP can support the expansion of innovative education models like Linked Learning, which integrates a program of study, work-based learning, and personalized student supports to help students make connections between what they’re studying in school and professional opportunities.23 In a survey, 80 percent of students who participated in a Linked Learning pathway said the model allowed them to apply what they were learning in a classroom setting to real-life opportunities, and 78 percent planned to pursue a postsecondary education immediately after high school.24

By investing in these approaches, California is removing logistical and administrative barriers, creating clearer pathways from high schools and community colleges to a four-year degree, and strengthening connections to the workforce—helping ensure students are prepared to succeed in college and their career.

2. Investing in robust data infrastructure

Robust data systems are essential for supporting informed decision-making by students and families and driving continuous improvement in postsecondary education. In California, state policymakers have invested in two data systems that support these goals.

- Cradle-to-Career (C2C) System: California’s statewide longitudinal data system (SLDS), C2C, connects data across nine agencies to serve as the state’s primary source of actionable student information. By breaking down barriers between agencies that do not typically share information with one another, C2C streamlines data sharing and empowers users to find deeper insights into student outcomes.25 The system is being implemented gradually over a five-year period, with some dashboards already publicly available and additional data tools planned for future rollout.26

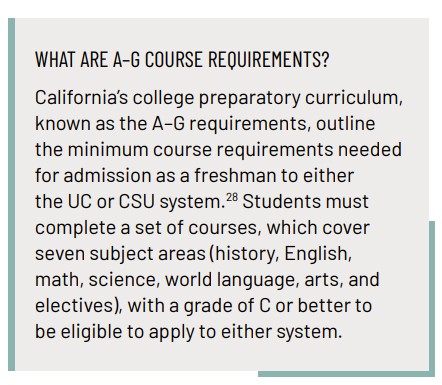

- California College Guidance Initiative (CCGI): CCGI manages californiacolleges.edu, the portal through which students apply to public colleges and universities in the state. As the legislatively authorized service provider for all school districts, CCGI gives every 6th through 12th grade student an account so they can access tools for college and career planning. Students can use the portal to complete career assessments, track A–G course completion and launch their Free Application for Federal Student Aid (FAFSA) or California Dream Act Application, California’s state alternative to the FAFSA for undocumented students.27 Parents and guardians can also monitor their children’s progress and access guidance through the portal.

Linking data systems to remove barriers in the college planning process

In 2021, as part of a larger bill to implement higher education budget provisions, the California legislature called for CCGI to be integrated with C2C.29 This linkage allows students to explore their college options while providing policymakers, educators, advocates, and researchers with information, through CCGI data, to guide targeted interventions and support.30 The integration has enabled innovative program and policy reforms.

For example, CSU leveraged these linked data systems to launch a direct admissions pilot program in partnership with the Riverside County Office of Education.31 High school seniors in Riverside County who were on track to meet or had already completed their A-G requirements were extended guaranteed admission to one of 10 participating CSU campuses before they submitted an application. The C2C-CCGI linkage identified which students were already eligible and which were close and could become eligible with targeted support. In its first year, CSU sent more than 17,000 direct admissions letters to students in Riverside County. Preliminary results showed a 15 percent increase in applications, a 9 percent increase in admissions, and a 43 percent increase in Riverside County students who committed to attend a participating CSU campus.32 In October 2025, policymakers passed legislation that will expand CSU’s direct admissions program to all CSU campuses with enrollment capacity. The law will take effect beginning in January 2026.33 California’s data infrastructure will provide CSU with the foundation needed for expanding this effort across the state.

By integrating key data sources and breaking down traditional data silos, California has created a system that can deliver essential information to those who need it. Investments in data architecture and infrastructure have improved access to higher education data and equip educators, counselors, and families with actionable insights to support students through the college application process. The CSU-Riverside County partnership is a prime example of how data can drive innovative reforms that benefit students and open pathways to college opportunity. Additional investment in the state’s SLDS could enhance data quality and usability, enabling users to more effectively track outcomes for students across different pathways.

3. Rethinking recruitment, admissions, and enrollment strategies at selective institutions

While California has taken several steps to expand and broaden college pathways, Latinx and Black students remain disproportionately underrepresented at selective institutions in the state. For example, at UCLA, one of the state’s most selective public universities, there was a 31 percentage point difference between the share of Latinx high school graduates (54 percent) and the share of Latinx students in the fall of 2023 (23 percent).34 While the long-term effects of Proposition 209 have impacted Black and Latinx enrollment at these selective campuses, the state has enacted several changes to its admissions process, including implementing holistic application reviews, eliminating legacy admissions policies, and prioritizing in-state students. These policies are intended to improve access to the UC system for students regardless of their background or circumstance.35

Implementing Holistic Application Reviews

A majority of selective colleges and universities across the country use some form of holistic review in their admissions process, a practice that considers factors beyond standardized test scores and GPA, such as geography, personal interests, academic growth, or life experiences that define a student.36 In 2002, UC implemented holistic review at six campuses, resulting in a 7 percent increase in the number of students of color at those campuses between 2002-2012.37 Today, all UC campuses use holistic review, and standardized test requirements were removed in 2020 across the system.38

Eliminating Legacy Admissions Policies

Legacy admissions policies, which give preference to applicants based on their relationship to alumni or donors, are relatively common at selective institutions. In 2022, almost one-third of all selective four-year institutions across the country considered legacy status in their admissions process. The practice is most prevalent at selective private institutions.39 Legacy admissions policies can increase a student’s chance of admission by 45 percentage points and disproportionately benefit wealthy, White students.40

Neither UC nor CSU considers legacy status in their admissions decisions, and in September 2025, new state legislation prohibited the practice at private colleges and universities in the state. The law allows the state’s Department of Justice to post names of institutions in violation of the ban. It will also require institutions that continue using the practice to submit detailed data about legacy status, donor status, race, county of residence, income bracket, and athletic status of newly enrolled students as well as the admission rate of students who receive a legacy preference or donor preference in admissions.41

California is one of the only states to extend legacy bans to private institutions, but the approach is not without limitations. Stanford University, for example, announced in the summer of 2025 that it will continue to grant legacy preferences in admissions decisions, despite the state ban. Eliminating legacy admissions is one step toward creating a more equitable higher education system. Doing so helps to promote fairness in the admissions process and ensures that access to opportunity is not influenced by inherited advantage.

Prioritizing Access for California Students

While some institutions of higher education expend significant resources on recruiting and enrolling out-of-state students who are willing to pay higher tuition fees, research finds that increasing nonresident enrollments can negatively impact access for students from low-income backgrounds and students of color, particularly at prestigious universities and in states with affirmative action bans.42 To ensure access to postsecondary opportunities for California residents, UC offers two paths into its system for local students: (1) a statewide guarantee for students who rank in the top 9 percent of all California high school students and (2) a local guarantee for students who rank in the top 9 percent of their graduating high school class.43 The system also aims to limit nonresident enrollment across its campuses.44

While top percent policies have resulted in modest improvements in campus diversity, the system’s most selective campuses continue to face limited enrollment capacity and remain out of reach for many California students.45

These race-neutral policies and practices seek to expand access to selective public and private institutions in the state and have demonstrated varying levels of effectiveness. While the impacts of the state’s legacy ban on selective private institutions are yet to be seen, holistic application reviews have been shown to be an effective strategy for addressing declines in Black and Latinx student enrollment at UC campuses, followed by the system’s statewide and local guarantee policies. In fall 2024, UC announced that it had admitted its largest class to date, with Black enrollment increasing by 5 percent and Latinx enrollment by 3 percent.46 Although there is no silver bullet, a comprehensive approach to recruitment, admissions, and enrollment that prioritizes equitable access to opportunity can affect change.

Policy recommendations for state leaders

Since voters banned affirmative action through Proposition 209, California has adopted a range of strategies to expand access to postsecondary opportunity. While there are opportunities to improve these efforts, they offer four valuable lessons for other states seeking to broaden and diversify pathways to a four-year degree following the SFFA decision.

These lessons include:

- Develop a broad set of pathways to college opportunity: Expanding access requires multiple, clearly defined on-ramps to college that meet students where they are, support them through graduation, and prepare them for the workforce. California’s investments, including in dual enrollment programs, streamlined transfer requirements, and career-focused pathways, are preparing students to succeed in postsecondary education and the workforce. Policymakers should consider their state context and identify where pathways can be built, streamlined, or expanded.

- Invest in robust data infrastructure: Strong data systems can transform how students, families, educators, and policymakers navigate and improve postsecondary opportunity. In California, the linkage between CCGI and C2C demonstrates how integrated data can streamline college planning and the application process. SLDSs give users a way to identify what obstacles exist within their state’s postsecondary system and to open new opportunities for innovation and reform. States should prioritize the continuous improvement of their data infrastructure, and carefully weigh the benefits and costs of developing, expanding, or maintaining an SLDS.

- Encourage institutions to rethink their recruitment, admissions, and enrollment strategies: The strategies institutions use to recruit, admit, and enroll their students shape who gains access to higher education. UC’s decision to move towards strategies like a holistic review process, combined with statewide and local guarantees, has helped increase access for Black and Latinx students. While institutions ultimately make their own admissions decisions, state policymakers can encourage colleges and universities to expand access in legally sound ways. Policymakers elsewhere should consider what incentives would encourage their state’s institutions to implement strategies like holistic reviews to improve access within their state context.

- Bring diverse voices to the table: No single sector can improve college access alone. The CSU-Riverside County partnership highlights how collaboration between K–12, higher education, and community partners can streamline pathways to college. The state’s CCAP program is an example of how policymakers have incentivized partnerships between the K–12 and postsecondary education sectors to the benefit of students and their communities. Decision-makers should incorporate a diverse set of voices, including students, practitioners, employers, and community partners, to ensure policy and practice reflect the needs of the students who these investments are intended to benefit.47 Cross-sector collaboration can accelerate innovation and improve outcomes.

California’s experience shows that expanding higher education access is not about a single program or policy, but about building a comprehensive system of pathways that support students at every stage of their educational journey. From incentivizing reforms in admissions and recruitment strategies to establishing data tools that smooth access and promote innovation across sectors, the state is demonstrating how clear, well-designed routes into and through higher education can strengthen equity and opportunity. As other states consider how to respond to the shifting legal landscape for college admissions, California’s investments offer lessons and strategies for ensuring that students—regardless of race, income, or background—can access and complete a high-quality postsecondary education.

Acknowledgements

This brief was funded by the Youth Thriving Through Learning Fund, which we thank for its support. The findings and conclusions presented in this brief are those of the authors alone, and do not necessarily reflect the opinions of the fund. We would like to thank the IHEP staff members who helped in this brief, including Mamie Voight, president and CEO; Kelly Leon, vice president of communications and government affairs; Erin Dunlop Velez, vice president of research; Lauren Bell, communications manager; and Rosario Durán and Michael Tidwell, research interns. We are very grateful to the field experts who lent their time for interviews with the IHEP team. We also thank IHEP consultant Vikash Reddy for offering his subject matter expertise, Sabrina Detlef for copyediting, and openbox9 for creative design and layout.

Endnotes

1 Leanne Davis, Jennifer Pocai, Jason L. Taylor, Sheena A. Kauppila, and Paul Rubin, Lighting the Path to Remove Systemic Barriers in Higher Education and Award Earned Postsecondary Credentials Through IHEP’s Degrees When Due Initiative (Institute for Higher Education Policy, April 2022), https://live-ihep-wp.pantheonsite.io/wp-content/uploads/2022/05/IHEP_DWD_fullreport_Web.pdf; and Karen Bussey, Kimberly Dancy, Alyse Gray Parker, Eleanor Eckerson Peters, and Mamie Voight, “Ending Legacy Admissions,” chapter 4 in “The Most Important Door That Will Ever Open”: Realizing the Mission of Higher Education through Equitable Admissions Policies (IHEP, June 2021), https://live-ihep-wp.pantheonsite.io/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/IHEP_JOYCE_REPORT_CH4_LEGACY-1.pdf.

2 Students for Fair Admissions, Inc. v. President and Fellows of Harvard College, 600 U.S. 181 (2023).

3 Zachary Bleemer, Diversity in University Admissions: Affirmative Action, Top Percent Policies, and Holistic Review (Berkeley Center for the Study of Higher Education, July 2019), https://cshe.berkeley.edu/publications/diversity-university-admissions-affirmative-action-percent-plans-and-holistic-review.

4 Zachary Bleemer, “The Effect of Affirmative Action Bans on College Enrollment,” UC-CHP Policy Brief 2024.1, September 2024, https://uccliometric.org/Policy_Briefs/UC-CHP-2024.1-AA-Bans.pdf.

5 The University of California, “The University of California Announces Record-Breaking Enrollment,” news release, January 9, 2025, https://www.universityofcalifornia.edu/news/university-california-announces-record-breaking-enrollment#:~:text=At%20just%20shy%20of%20300%2C000,for%20advanced%20education%20and%20research; and The California State University, “Enrollment Data Dashboard,” https://tableau.calstate.edu/views/SelfEnrollmentDashboard/EnrollmentSummary?iframeSizedToWindow=true&%3Aembed=y&%3AshowAppBanner=false&%3Adisplay_count=no&%3AshowVizHome=no.

6 Jason L. Taylor, Taryn Ozuna Allen, Brian P. An, Christine Denecker, Julie A. Edmunds, John Fink, Matt S. Giani, Michelle Hodara, Xiaodan Hu, Barbara F. Tobolowsky, and Willie Chen, Research Priorities for Advancing Equitable Dual Enrollment Policy and Practice (University of Utah, July 2022), https://cherp.utah.edu/_resources/documents/publications/research_priorities_for_advancing_equitable_dual_enrollment_policy_and_practice.pdf.

7 Rachel Yang Zhou, Olga Rodriguez, Eric Assan, and Daniel Payares-Montoya, “Dual Enrollment in California: Fact Sheet,” Public Policy Institute of California, accessed October 24, 2025, https://www.ppic.org/publication/fact-sheet-dual-enrollment-in-california/.

8 California Department of Education, “Request for Applications: College and Career Access Pathways Grant,” https://www.cde.ca.gov/fg/fo/r17/ccap24rfa.asp.

9 Zhou, Rodriguez, Assan, and Payares-Montoya, “Dual Enrollment in California.”

10 Olga Rodríguez, Daniel Payares‑Montoya, Iwunze Ugo, Niu Gao, and Stephanie Barton, “Policy Brief: Improving College Access and Success through Dual Enrollment,” Public Policy Institute of California, August 2023, https://www.ppic.org/publication/policy-brief-improving-college-access-and-success-through-dual-enrollment/.

11 EdTrust-West, Jumpstarting California Towards Universal Dual Enrollment (Education Trust-West, February 2025), https://west.edtrust.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/ETW_2025_JumpstartingCAUniversalDualEnrollment_DIGITAL.pdf.

12 IHEP analysis of DataQuest information from California Department of Education. See “2021–22 College‑Going Rate for California High School Students by Postsecondary Institution Type,” last reviewed Wednesday, September 10, 2025, https://dq.cde.ca.gov/DataQuest/DQCensus/CGR.aspx?cds=00&agglevel=State&year=2021‑22.

13 The Campaign for College Opportunity, 10 Years After Historic Transfer Reform: How Far Have We Come and Where Do We Need to Go? (The Campaign for College Opportunity, July 2020), https://collegecampaign.org/wp-content/uploads/imported-files/10-Years-After-ADT-Brief.pdf and Vikash Reddy and Jessie Ryan, Chutes or Ladders? Strengthening California Community College Transfer So More Students Earn the Degrees They Seek (The Campaign for College Opportunity, June 2021), https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED613728.

14 California Community Colleges, “Associate Degree for Transfer,” https://icangotocollege.com/associate-degree-for-transfer?sitekey=adegree.

15 Vikash Reddy and Jessie Ryan, Chutes or Ladders? Strengthening California Community College Transfer So More Students Earn the Degrees They Seek.

16 Ashley A. Smith, “Cal State Extends General Education Requirements for Transfers to First-Time Freshmen,” EdSource, March 27, 2024, https://edsource.org/2024/cal-state-extends-general-education-requirements-for-transfers-to-first-time-freshmen/708595.

17 California Community Colleges, “Dual Admission,” https://www.cccco.edu/About-Us/Chancellors-Office/Divisions/Educational-Services-and-Support/dual-admission.

18 California Community Colleges, “Key Facts,” https://www.cccco.edu/about-us/key-facts.

19 California Community Colleges Chancellor’s Office, 2025, “Dual Admission,” https://www.cccco.edu/About-Us/Chancellors-Office/Divisions/Educational-Services-and-Support/dual-admission; and California Community Colleges, “Associate Degree for Transfer,”https://icangotocollege.com/associate-degree-for-transfer.

20 Gallup and Lumina Foundation, The State of Higher Education 2025 (Gallup and Lumina Foundation, 2025), https://www.gallup.com/analytics/644939/state-of-higher-education.aspx?thank-you-report-form=1.

21 California Department of Education, “Golden State Pathways Program Planning and Implementation Grant,” last modified April 23, 2024, https://www.cde.ca.gov/fg/fo/profile.asp?id=6127.

22 California Department of Education, “Golden State Pathways Program”; and California Legislature, Education Code, Division 4, Title 2, Part 28, Chapter 16.1 (Golden State Pathways Program), https://leginfo.legislature.ca.gov/faces/codes_displayText.xhtml?lawCode=EDC&division=4.&title=2.&part=28.&chapter=16.1.&article=.

23 Linked Learning Alliance, “The Linked Learning Approach,” https://www.linkedlearning.org/about/linked-learning-approach; and ConnectED, “What Is Linked Learning?” https://connectednational.org/meet/about/what-is-linked-learning/.

24 Linked Learning Alliance, “Linked Learning Student Survey 2024: Topline Findings,” September 2024, https://d985fra41m798.cloudfront.net/resources/2024StudentSurvey_ToplineFindings_2024Aug30.pdf?mtime=20240916134009&focal=none.

25 California Cradle to Career Data System, “Connecting Insights Across Silos,” June 3, 2025, https://c2c.ca.gov/resources/connecting-insights-across-silos/; and California Cradle to Career Data System, “California Cradle-to-Career Data System Informational One-Pager,” May 17, 2023, https://c2c.ca.gov/resources/cradle-to-career-informational-one-pager/.

26 California Cradle to Career Data System, “Cradle-to-Career Dashboards,” n.d. https://c2c.ca.gov/cradle-to-career-dashboards/; California Cradle to Career Data System, “California Cradle-to-Career Data System 2023–24 Workplan,” n.d., https://c2c.ca.gov/wp-content/uploads/2023/10/5-year-timeline-2023.pdf; and California Cradle to Career Data System, “Roadmap & Progress,” n.d., https://c2c.ca.gov/roadmap-progress/.

27 California Department of Education, “California College Guidance Initiative Statewide Rollout,” September 24, 2024, https://www.cde.ca.gov/ds/sp/cl/ccgirollout20240924.asp; California Department of Education, “CCGI Flash #2: Transcript-Informed Partner Accounts to Students in Grades 9–12; Key Simultaneous Efforts to Streamline Processes,” September 20, 2024, https://www.cde.ca.gov/ds/sp/cl/ccgiflash2.asp; and California Department of Education, “California College Guidance Initiative Statewide Rollout.”

28 California Department of Education, “Courses Required for California Public University,” last reviewed August 21, 2024, accessed September 10, 2025, https://www.cde.ca.gov/ci/gs/hs/hsgrtable.asp.

29 California Legislature, AB 132: Postsecondary Education Trailer Bill, Chapter 144 (2021), https://leginfo.legislature.ca.gov/faces/billTextClient.xhtml?bill_id=202120220AB132.

30 California College Guidance Initiative, “Who We Are,” https://cacollegeguidance.org/who-we-are/.

31 California State University, “The California State University and Riverside County Office of Education Partnership,” https://www.calstate.edu/impact-of-the-csu/community/Pages/riverside-county-office-of-education-partnership.aspx; and Sonoma State University, “Sonoma State One of 10 CSUs in Direct‑Admission Pilot Program,” SSU News, November 5, 2024, https://news.sonoma.edu/articles/2024/sonoma-state-one-10-csus-direct-admission-pilot-program.

32 Janiel Santos and Michael Tidwell, “Direct Admissions Expands College Opportunity in California. Three Lessons from California State University’s Pilot,” blog post, Institute for Higher Education Policy, September 4, 2025, https://www.ihep.org/direct-admissions-expands-college-opportunity-in-california-three-lessons-from-california-state-universitys-pilot/.

33 California Legislature, Senate Bill 640: Public Postsecondary Education: Admission, Transfer, and Enrollment, 2025–2026 Regular Session, https://legiscan.com/CA/text/SB640/id/3135035.

34 IHEP analysis of DataQuest information from California Department of Education, “2022–23 Four‑Year Adjusted Cohort Graduation Rate,” accessed September 10, 2025, https://dq.cde.ca.gov/dataquest/dqcensus/CohRate.aspx?cds=00&agglevel=State&year=2022-23&initrow=&ro=y; National Center for Education Statistics. IPEDS Summary Tables: Report 240 (Institutional Summary Tables for 2023). Accessed September 10, 2025. https://nces.ed.gov/ipeds/SummaryTables/report/240?templateId=2400&year=2023&expand_by=0&tt=institutional&instType=2&sid=96869cba-4127-4a4b-a358-4281751c1ce6.

35 Zachary Bleemer, Affirmative Action, Mismatch, and Economic Mobility After California’s Proposition 209 (Berkeley Center for Studies in Higher Education, August 2020), https://cshe.berkeley.edu/publications/affirmative-action-mismatch-and-economic-mobility-after-california%E2%80%99s-proposition-209.

36 Michael Bastedo, Nicholas A. Bowman, Kristen M. Glasener, Jandi L. Kelly, and Emily Bausch, “What Is Holistic Review in College Admissions?” policy brief, University of Michigan Center for the Study of Higher and Postsecondary Education, November 2017, https://websites.umich.edu/~bastedo/policybriefs/Bastedo-holisticreview.pdf; and Art L. Coleman and Jamie L. Keith, Understanding Holistic Review in Higher Education Admissions: Guiding Principles and Model Illustrations (College Board & Education Counsel, 2018), https://educationcounsel.com/our_work/publications/roadmap-framework/understanding-holistic-review-in-higher-education-admissions-guiding-principles-and-model-illustrations-2.

37 Zachary Bleemer, “Affirmative Action and Its Race-Neutral Alternatives,” Journal of Public Economics 220 (2023): article 104839, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpubeco.2023.104839.

38 University of California, “First-Year Requirements,” n.d., https://admission.universityofcalifornia.edu/counselors/preparing-freshman-students/freshman-requirements.html; and Apollonia Morrill, “How the University of California Evaluated Student Applications,” University of California (website), October 31, 2024, https://www.universityofcalifornia.edu/news/how-the-university-of-california-evaluates-student-applications.

39 Marián Vargas and Sean Tierney, “Legacy Looms Large in College Admissions, Perpetuating Inequities in College Access,” blog post, Institute for Higher Education Policy, July 1, 2024, https://www.ihep.org/legacy-looms-large-in-college-admissions-perpetuating-inequities/.

40 Bussey, Dancy, Gray Parker, Eckerson Peters, and Voight, “Ending Legacy Admissions,” https://live-ihep-wp.pantheonsite.io/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/IHEP_JOYCE_REPORT_CH4_LEGACY-1.pdf; and Michael Hurwitz, “The Impact of Legacy Status on Undergraduate Admissions at Elite Colleges and Universities,” Economics of Education Review 30, no. 3 (2011): 480–92, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econedurev.2010.12.002.

41 California Legislature, AB 1780: Independent Institutions of Higher Education: Legacy and Donor Preference in Admissions: Prohibition, Chapter 1006 (2024), https://leginfo.legislature.ca.gov/faces/billNavClient.xhtml?bill_id=202320240AB1780.

42 Ozan Jaquette, Brad Curs, and Julie Posselt, “Tuition Rich, Mission Poor: Nonresident Enrollment Growth and the Socioeconomic and Racial Composition of Public Research Universities,” The Journal of Higher Education 87, no. 5 (2016): 635–673, https://doi.org/10.1080/00221546.2016.11777417.

43 University of California, “The 411 on ELC: Eligibility in the Local Context,” PowerPoint slides, April 29, 2025, https://admission.universityofcalifornia.edu/counselors/_files/documents/counselor-webinars/hs-webinar-411-on-elc.pdf; and University of California, Admissions, “California Residents,” accessed September 10, 2025, https://admission.universityofcalifornia.edu/admission-requirements/first-year-requirements/california-residents/.

44 Salwa Meghjee, “UC Board of Regents Should Reject Nonresident Enrollment Cap and Tuition Increase,” The Daily Californian, March 8, 2019, https://www.dailycal.org/archives/uc-board-of-regents-should-reject-nonresident-enrollment-cap-and-tuition-increase/article_d6755e92-3ce7-5b42-8483-778e5daae144.html.

45 Michal Kurlaender, Sarah Reber, and Jesse Rothstein, “UC Regents Should Consider All Evidence and Options in Decision on Admissions Policy,” PACE (Policy Analysis for California Education), April 22, 2020, https://edpolicyinca.org/newsroom/uc-regents-should-consider-all-evidence-and-options-decision-admissions-policy; University of California, “UC Board of Regents Approves Policy on Nonresident Student Enrollment,” press release, May 18, 2017, https://www.universityofcalifornia.edu/press-room/uc-board-regents-approves-policy-nonresident-student-enrollment; and Zachary Bleemer, “Affirmative Action and Its Race-Neutral Alternatives,” https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpubeco.2023.104839.

46 University of California, “The University of California Announces Record-Breaking Enrollment,” news release, January 9, 2025, https://www.universityofcalifornia.edu/news/university-california-announces-record-breaking-enrollment; Jaweed Kaleem, “Under Pressure, UC Admits a Record Number of Californians; Racial Diversity Remains Strong,” Los Angeles Times, July 28, 2025, https://www.latimes.com/california/story/2025-07-28/uc-fall-2025-admissions-record-number-from-california-international-students-racial-diversity; and Bleemer, “Affirmative Action and Its Race-Neutral Alternatives.”

47 Advisory Committee for Equitable Policymaking Processes, “Opening the Promise:” The Five Principles of Equitable Policymaking (Institute for Higher Education Policy, January 2022), https://live-ihep-wp.pantheonsite.io/wp-content/uploads/2022/01/IHEP_equitable_policy_principles_brief_final_web2.pdf.