IHEP VP of Research and Policy Testifies Before Massachusetts Board of Higher Education

Published Feb 13, 2024

On February 13, 2024, IHEP Vice President of Policy Research Diane Cheng testified before the Massachusetts Board of Higher Education’s Finance and Administrative Policy – Advisory Council Meeting Agenda about how to design equitable affordability programs that meet the needs of students from low income backgrounds. Click here to view her presentation and access the full written testimony here.

“Good afternoon, Chair Gabrieli, FAAP Co-Chair LaRock, members of the Finance and Administrative Policy Advisory Council, and members of the Board of Higher Education. Thank you for the opportunity to speak today about the importance of strengthening investment in college affordability. My name is Diane Cheng and I am the Vice President of Research and Policy at the Institute for Higher Education Policy (IHEP).

IHEP is a nonprofit, nonpartisan research and advocacy organization that has been working to expand college access and success for all students for over 30 years. We advocate for systemic change in higher education to advance equitable outcomes and generational impact for communities historically marginalized on the basis of race, ethnicity, or income.

We know that the benefits of higher education extend far beyond the individual, enriching families, communities, and the nation as a whole – but only if people can afford to attend. The playing field for higher education is uneven. We’re seeing troubling trends that show disparities in enrollment, completion rates, and debt loads along racial and socioeconomic lines.

The students who have the most to gain from higher education are the same students who are most likely to be forced to stop out when the cost of college is too high – or to not be able to enroll in the first place. It’s time to bridge the affordability gap by investing in solutions. We commend the Commonwealth for its strong support for public higher education and investing in efforts to make public colleges more affordable for students.

In my remarks today, I will share recommended principles for state affordability programs, discuss how MASSGrant Plus Expansion (MGPE) aligns with some of those principles, and recommend ways to expand MGPE to provide a stronger affordability guarantee for students attending public 2-year and 4-year colleges in Massachusetts.

Recommended principles for state affordability programs

These student aid programs can have different names, including “free college”, “college promise”, and “debt-free college”. The following principles would address the greatest affordability challenges, support college enrollment and completion, and reduce inequities. Targeted needbased aid programs have a proven track record of disrupting inequities in college access, persistence, and success. Helping more students get to and through college can also help states meet their workforce needs.

Invest first and foremost in students from low-income backgrounds

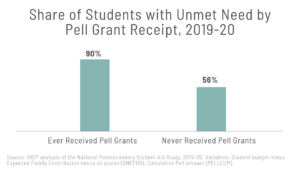

Pell Grant recipients are more likely to have unmet financial need than students who do not receive Pell Grants, including substantial financial need beyond tuition and fees.1 Data from NPSAS:20 show that 90 percent of students who received a federal Pell Grant at least once face unmet need, compared to 56 percent of students who never received a Pell Grant.

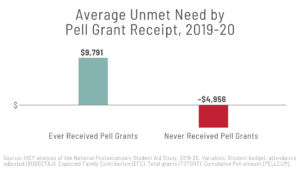

Students who received a Pell Grant at least once face average unmet need of about $9,800, while students who never received a Pell Grant are typically able to fully cover college costs using grants and family resources, with an estimated $5,000 to spare.

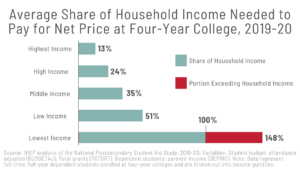

Another measure of college affordability is the share of household income students would need to contribute to cover the net price of college, defined as the full cost of attendance minus grants and scholarships. Data from four-year colleges nationally shows the average net price for dependent students enrolled full time vastly exceeds the resources available to students from families from the bottom two income quintiles. In fact, to pay the cost of full-time attendance at a four-year college, families with the lowest incomes would need to contribute almost 150 percent of their household income.

Fund non-tuition expenses for students from low-income backgrounds

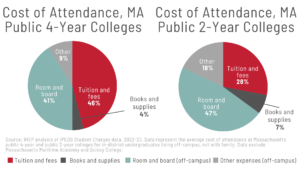

According to the most recently available IPEDS data, tuition and fees only composed 28 percent, on average, of the total cost of attendance for students attending Massachusetts community colleges and 46 percent of total costs for students attending Massachusetts public 4-year colleges. Just looking at tuition and fees leaves out about $15,000 in college costs for Massachusetts public 4-year college students and community college students. Other key components of cost of attendance include books and supplies, room and board, transportation, childcare, and other expenses. Living expenses make up half of average expenses at Massachusetts public 4-year colleges and almost two-thirds of expenses at Massachusetts

community colleges.

Provide state support through a first-dollar, not last-dollar approach

This is particularly important for state free college plans that only cover tuition and fees, since those expenses may be partially or fully covered by federal aid. Many state free college programs are last-dollar, meaning that funding is provided to cover all remaining tuition and fees only after other sources of grant aid are applied. Because the federal Pell Grant and other need-based sources of aid provide substantial grant amounts to students from low-income backgrounds, last dollar programs often provide these students limited additional support, if any. Previous IHEP research on last-dollar programs in New York and Tennessee found that students from low-income backgrounds are particularly unlikely to benefit from these types of programs, even though those students continue to face difficulties covering housing, meals, and other basic needs.2

In contrast, first-dollar models provide students funding equivalent to full tuition and fees, allowing them to use other sources of grant aid for living expenses and other costs of attending college. While a first-dollar model is ideal, a middle-dollar model would be preferable to a last dollar model. A middle-dollar approach would provide an additional stipend for students whose tuition and fees are covered entirely or almost entirely by other aid.

Include both public four-year colleges and community colleges

Though some free college programs are focused on community colleges, including public 4-year colleges in these programs would help preserve student choice. Students and families should be able to pursue the type of college, program, and credential that best serve their educational and career goals.

Avoid restrictive or punitive eligibility requirements

For example, academic requirements and post-college residency requirements can disproportionately exclude students from low-income backgrounds and punish students for pursuing work or family commitments in another state after college.

Recommended Improvements to MASSGrant Plus Expansion MASSGrant Plus Expansion

(MGPE) already meets some of the principles we outlined. It provides the greatest benefit to students eligible for federal need-based Pell Grants. By covering public 2-year and 4-year colleges, MGPE helps students enroll in the college that is the best fit for them. For Pell-eligible students, this plan covers some nontuition costs – up to $1,200 in books and supplies. It also avoids restrictive participation requirements. However, MGPE has some limitations. It is last-dollar, so students won’t receive aid through MGPE if their Pell Grants fully cover their tuition, fees, books, and supplies. It also doesn’t cover living expenses.

To provide students a stronger affordability guarantee, we recommend expanding MGPE to include living expenses. The ideal approach is to cover the full amount of students’ unmet financial need, which represents the gap between their total college costs (including both tuition and non-tuition expenses) and the funds available to them through grant aid and family resources. This is the model proposed in the CHERISH Act, where state financial aid would cover the difference between full cost of attendance and a reasonable student contribution (including Pell Grants, other institutional financial aid, a family contribution, and student earnings). The Massachusetts Association of Community Colleges’ (MACC) recent initial report acknowledges that “low-income students continue to face financial barriers beyond tuition and fees to attending and completing community college” and two of its models (preferred model and “living expenses for low income”) include some coverage of living expenses for students with lower incomes.3

If it is not feasible to fully cover the unmet need of students from low-income backgrounds, MGPE should provide a stipend to cover living expenses beyond tuition. Policymakers should consider higher stipends than the $2,000 in some proposals. For example, California State University trustees recently voted for stipends up to $5,000 to cover living expenses.4 If MGPE were expanded to cover living expenses, then it is less important whether the state funding is applied through a first-, middle-, or last dollar model.

Finally, we recommend starting this expansion with students who are eligible for Pell Grants. While benefits could be extended to include other students in future years, it is crucial to first focus on students with the greatest financial need, who face the most barriers to afford, attend, and complete college. This approach would provide a robust version of “free college” for students who would struggle most to otherwise cover college costs, and help make public colleges in the Commonwealth accessible to more students.

We commend the Commonwealth for investing in efforts to make public colleges more affordable for students. Expanding those efforts to cover living expenses for students from low-income backgrounds will help those students get to and though college, ultimately benefiting them, their families, communities, and the nation overall.